Who, When, Why, Where

Who

One interesting fact I have learned from studying the statistics of all the cat rescues I have done is that it is the youngsters who are most likely to climb a tree and get stuck. In fact, 73% of all the rescues I have done are for cats who are two years old and younger, and more than half of all rescues are for cats that are one year old and younger. Is this because older cats are less likely to climb the tree, or is it because they are more likely to know how to climb down? Is it because the entire cat population here is made up of more young cats than old ones? I don’t know the answer, but, regardless, any cat of any age at any time can get stuck in a tree.

Most people assume that indoor cats don’t get stuck in a tree for obvious reasons, but it is actually very common. In fact, once an indoor cat escapes his house, he is more likely to get stuck in a tree for two reasons: (1) his outside territory is more likely to be claimed and guarded by another cat or dog who will respond to his intrusion by chasing him up a tree, and (2) as an inside cat, he has never had an opportunity to learn how to climb down a tree.

One would think that cats that have been declawed would not be able to climb a tree, but it actually appears to be possible under certain conditions. First, let’s set aside the ethical issues involved with declawing and letting a declawed cat outside. If a cat has had all four paws declawed, then he will not be able to climb a tree in the usual sense. He may, however, be able to jump up to low limbs on some trees or get a running start and use his momentum to help him jump to higher limbs. Once in the tree, he may be able to go fairly high as long as the limbs are within his acceptable stepping and jumping distance.

If only the front paws have been declawed, then it may be possible to climb a tree as long as the tree trunk is small enough that the cat can reach around to the backside of the trunk far enough with his front paws to pull himself upright. It’s the back legs that provide most of the upward push and support in a climb, but it would still be more difficult for a cat to climb this way because he would never be able to transfer a portion of his weight to his front paws. Climbing a tree with a large trunk should not be possible since he won’t be able to reach around it, and he has no way to grab the surface well enough to hold himself upright.

When

I don’t have any data on the timing of a cat’s ascent into the tree, and I have not informally observed any sign of a preference for daytime or nighttime. If we had that data, I suspect it would not be very revealing. However, I have noticed a seasonal pattern over the years. I have found that I have half as many rescues during the four months of June through September compared to both of the other four-month periods in the year. I am in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where those are the hottest months of the year, and I have heard from other rescuers in the South that they have noticed a slump during the summer as well. Some rescuers in cold climates have reported that the summer is their busiest time of the year and winter is their slowest, so it appears that it is the temperature extremes that are keeping cats mostly grounded. Every part of the country has times of extreme temperatures, but where they are more frequent and longer, the effects are more obvious.

If temperature extremes are keeping cats from climbing trees, why should that be? Are dogs too hot or cold to chase them? Are cats too

hot or cold to get the zoomies? Are people less likely to search for them and find them? I don’t know, but I suspect it’s just because cats are not likely to be as active when it’s very hot or cold. Indoor-outdoor cats may be spending less time outside, and outdoor cats may be less active, so there are fewer opportunities for them to get into tree-climbing trouble.

Why

Cats climb trees for a number of reasons. Some cat owners report that they saw their cat chasing a squirrel or bird, and, more often, some people report seeing the cat being chased up the tree by a dog or another cat. Most of the time, however, it seems that no one saw the cat climb the tree, and we can only guess the reason. Some cats may get severely spooked by a sudden, loud noise or commotion and feel the need to escape immediately. Some cats may get a bad case of the “zoomies,” and, if there is a tree nearby when that happens, they may run up the tree and may keep going until they are too high. We know that cats are commonly chased up a tree by a dog, coyote, or another cat, but we don’t know for sure if that is the most common reason.

Where

Finding a cat that is stuck in a tree can be surprisingly difficult. If your cat is missing and you suspect he might be in a tree, or if you hear a cat crying but can’t locate the source, it is helpful to know where and how to look in a tree to find him. It is easier in the winter months when many trees are bare of foliage, but it can still be surprisingly difficult to see a cat even then. When foliage from the tree or vines is present, it is even more difficult. To improve your chances of finding the cat, it is important to search from many vantage points from far away on all sides to directly beneath the tree. Binoculars are helpful during the day, and a strong flashlight can be used in the darkness to search for the cat’s “eye-shine.” Cat eyes will reflect the light from your flashlight back to you making them very easy to see in the darkness. However, keep in mind that you will not see a reflection if the cat’s eyes are closed, the cat is not facing you, or there is no direct line of sight to the cat’s eyes from both the flashlight and your eyes at the same time, so failing to see eye-shine does not mean the cat is not in the tree.

Where a cat comes to a rest in the tree depends greatly on the characteristics of the tree he is climbing and his motivation for climbing. If the cat is climbing to escape a chasing predator, then he will climb as high as needed for him to feel safely out of danger. Some cats may feel safe just ten feet high while others may climb 80 feet before they feel safe. If the cat is chasing a squirrel, he will probably stop climbing as soon as he realizes that chasing a squirrel in a tree is hopeless. Regardless of his motivation, at some point, he will stop to look for a comfortable resting spot. Hanging vertically on the trunk of the tree is very tiring, so he will either step onto a nearby limb or stop in a fork or

any place that offers enough of a horizontal surface for him to stand or sit.

If the cat rests on a small limb, he will quickly feel how uncomfortable it is and how unstable he feels on it, so he may look for a larger one. If he can’t climb down, he may climb higher and move from one limb to another until he finds something that is adequate. Wherever he goes, he is looking for comfort and stability. Sometimes, his search for a more comfortable spot just makes matters worse, since the limbs generally become smaller as he climbs higher. He may find a way to go down to a point where he is more comfortable, but eventually he will settle in the best spot he can find in his limited range of travel.

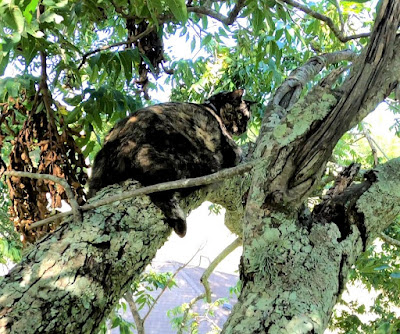

In my experience in my region, I find that most cats will perch, as is generally expected, on a limb immediately next to the trunk of the tree. The largest part of the limb is there next to the trunk, and it supports them while the trunk keeps them from falling to one side. The limb they choose may be low, high, or in-between, but if you are looking for a cat in a tree, the crotches all along the trunk would be the first place to look. In the first picture (below, left), Elizabeth perched in the crotch of the first significant limb she found, while Hippy, (below, right) had to climb much higher before he found a comfortable limb.

If the cat finds two closely-spaced limbs roughly level with each other, he may choose to spread his body across both of them, especially when the limbs are very small. Zephyr, in the picture below, spent one long, uncomfortable night standing on two tiny limbs.

Cats also often go far out a limb and find a place to settle there. Rather than balance on one small limb, they prefer places that offer a broader area of support such as horizontal fork in the limb or places where there are shoots off to both sides of the limb. By spreading their body across two or more small limbs, they reduce their chance of falling and gain more comfort and stability. Oscar, in the first picture below, spread his body across both legs of a horizontal fork, while Simba, in the second picture below, straddled one limb and stretched over another one to get some rest.

If the limb is mostly horizontal and roughly the size of their body, they sometimes stretch out on their belly in line with the limb to get some rest as Cookie demonstrates in the first picture below. On very large limbs, they can stretch out comfortably anywhere along the limb with very little concern about falling as Lucky did in this massive Live Oak tree (second picture below).

Sometimes, when a cat gets hot or exhausted, he will drape his body limply across a limb like a wet rag hanging out to dry with his front legs dangling off to one side and his back legs dangling off the other side. Tigger (first picture below) had spent five hot Summer days in the tree and was too exhausted to stand or sit, while Cake (second picture below) had spent less time in a milder season, but he, too, needed to rest. To an observer, they appear to be dead. They are too tired to stand or sit, and draping their body over the limb like that gives them a chance to rest or sleep without worrying about falling. It’s not comfortable, but it’s the best they can do at the time.

Some cats are not content to stop on the lower, large limbs where they would be safe and comfortable. Instead, they climb to the extreme tip top of the tree or go far out to the wispy tips of a long, high limb. Anastasia (below, left) was about 90 feet high and all exposed at the extreme tip of a long branch, and Trouble went all the way out to the thin tips which were just barely able to support his weight. These can be the most challenging cases for a rescuer, but they can also be among the most memorable.

It can be very difficult to see a cat in a tree from the

ground, and, in some cases, it’s impossible. I have seen cases, such as Oliver in the first picture below, where a cat curled up in a nest and could not be seen from the ground unless it stood up and looked over the edge. Even worse are the cases where the top portion of a tree has broken off and exposed a cavity in the top of the remaining spar where a cat can rest completely out of view of anyone on the ground as Kingsley demonstrates in the second picture below. In a spot like this, a cat can sleep without ever worrying about rolling out of the tree, and, if you ever find a cat skeleton in a tree, this is where you are likely to find it.

I am often asked about the highest I have climbed to rescue a cat, and, currently, my answer is 100 feet. Most of the rescues I have done are under 40 feet, though several have been up to 70 feet. These are the heights to be expected for the trees in this region. While there are many very tall trees here, it has been rare for me, so far, to have to rescue a cat in one. In the Pacific Northwest, however, extremely tall conifers are very common, and Thomas Otto and Shaun Sears of Canopy Cat Rescue frequently rescue cats well over 100 feet high. The last time I checked, their highest rescue was at 170 feet. While most cats don’t climb that high, there will always be those exceptional cats, and the only

limit to the height to which a cat will climb is the tree itself.

Most people, including myself, are very inaccurate at estimating the height of a cat in a tree. It’s difficult to judge the height without some experience combined with some kind of objective means of measuring it. The way I measure is by putting black marks on my climbing rope at 10-feet intervals and counting them either when installing or uninstalling the rope. The distance between 10-feet marks can easily be estimated.

Behavior >>>